Why We Need to Talk About Organ Donation

Your body is a treasure trove of spare parts! Learn about organ donation and the slightly weird, but wonderful, ways it can give someone a whole new story.

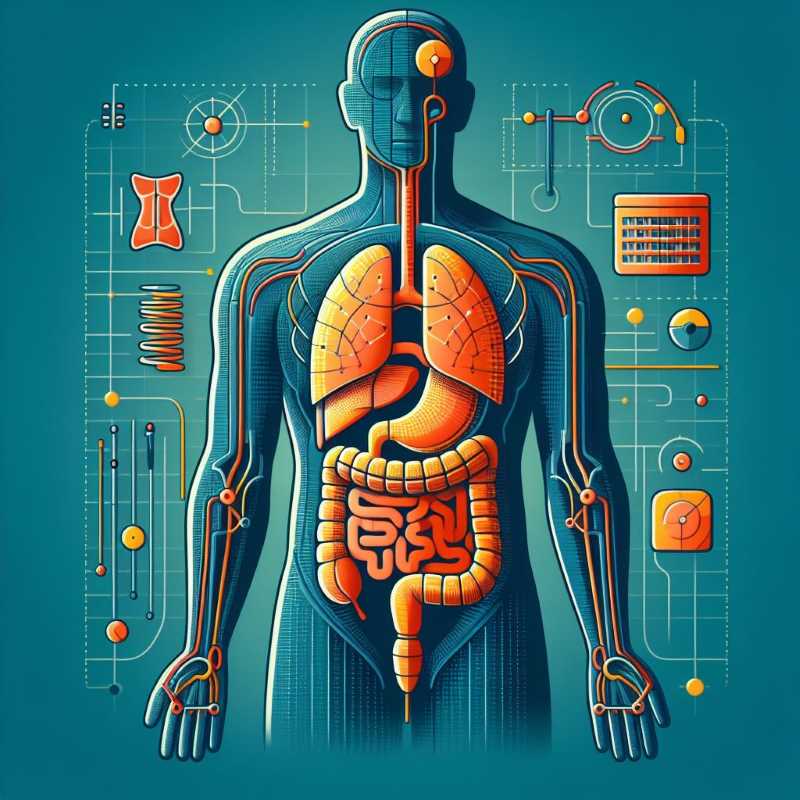

The human body is a wondrous, often infuriating machine. A collection of squelches and creaks, electrical impulses and chemical reactions, all held together by a stubborn force we call 'life'. But like any delicate device, it breaks down. Parts wear out, systems fail, and occasionally the whole thing just… stops.

That's where the transplant comes in – consider it to be the spare parts store for your fleshy vehicle. Need a new kidney? We've got a few on ice. Heart not pumping like it used to? Step right up, we'll size you for a fresh one. It's a medical miracle cloaked in the slightly unsettling practicality of automotive repair.