Aimé Painé, the tireless struggle for the Mapuche identity

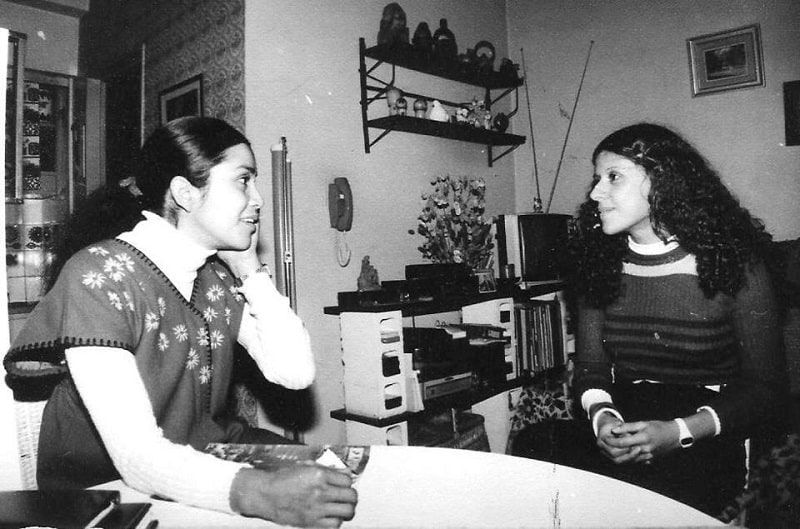

Aimé Painé was born 78 years ago, the first Mapuche singer to perform in traditional attire and also the architect of the recovery of the beautiful songbook of the grandmothers of her community. Her biographer Cristina Rafanelli expands on some aspects of the work and life of "a great fighter".

78 years ago was born the first Mapuche singer to perform in traditional attire and also the architect of the recovery of the beautiful songbook of the grandmothers of her community. In this interview, her biographer Cristina Rafanelli expands on some aspects of the work and life of "a great fighter", Aimé Painé.

Aimé Painé was born on August 23, 1943 in Ing. Huergo, Río Negro. She was recorded as Olga Elisa Painé thanks to a system that maintained that the Mapuche-Tehuelche people no longer existed. Torn from her land, her family, and her community when she was three years old, she was raised among orphanages, boarding schools, and Catholic choirs. When she grew up she looked for her family, changed her name, and amid the Civil-Military Dictatorship, she turned to the repertoire in the Mapudungun language to become the first Mapuche singer of international renown.

Aimé died in September 1987 in Asunción, Paraguay, at the age of 44. He never recorded an album and perhaps that is why his work was ignored for a long time. Cristina Rafanelli was one of the first journalists to disseminate Painé's work and wrote the first version of his biography in 2011, published by Biblos and sponsored by the Fundación Desde América with the support of anthropologist Carlos Martínez Sarasola.

"It was difficult to research. Nobody talked about Aimé. She didn't talk about her mother. She was kind of hushed. For 25 years nobody talked about Aimé Painé. Somehow, when the first book came out, it was about making visible the life of a great fighter as well as a great artist," she explains.

"An incredible fighter who tried to give her people back their lost dignity. She found that the grandmothers did not want to speak the language, they had stopped transmitting their culture through orality. After the Desert Campaign, and with all the dignity of accepting a defeat so that the new generations could survive, that chain had been cut. That is why Aimé's courage. She is beginning to recover that culture little by little".

Almost at the same time as that first biography - and in parallel with the revival of the defense of Mapuche territory - a street was named after Aimé Painé in Puerto Madero, Buenos Aires, and she was included in the Women's Hall in the Casa Rosada.

Therefore, in 2020, Rafanelli published an expanded version of her book Aimé Painé. La Voz del Pueblo Mapuche ("Aimé Painé. The Voice of the Mapuche People"), published by Espacio Hudson, with new testimonies and more than 50 photographs. In this interview, the writer reviews the most important aspects of Aimé Painé's life and the difference between the context of that first biography and the current one.

How did you meet Aimé?

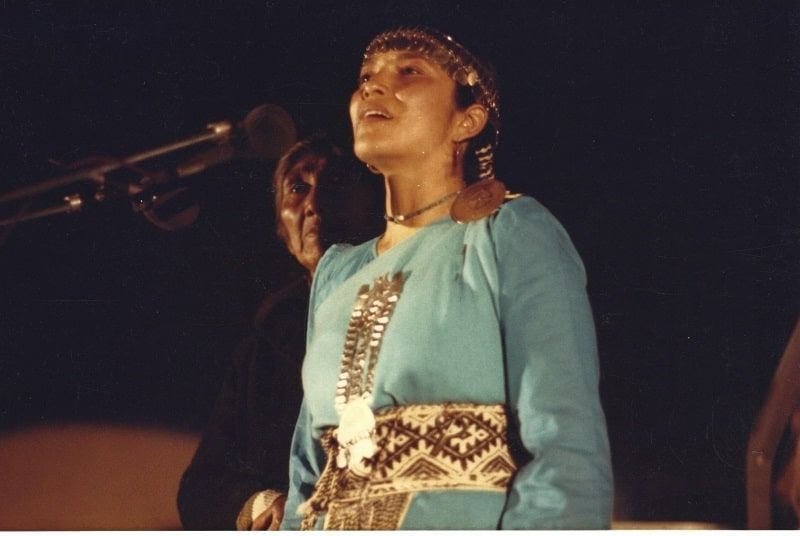

I met her in 1979 when I was writing for Expreso Imaginario. We went to cover an exhibition of Mapuche handicrafts with the photographer, who at that time was the director of the magazine. We went to chat with the person who organized it and she was the one who told me "Stay because now a singer is coming that I want you to meet". I stayed for her presentation and the truth is that it was something incredible because nobody at that time was wearing Ttrarilonko, with the breastplate and the coins, the old-fashioned way. But what fascinated me the most was her communication with people. She spoke in their language to an audience of Mapuches who had come to live in the city.

I wrote about her in the magazine in a three-page interview that was published under the name "El canto de una raza" (The song of a race). Aimé was very happy with the article because it was a very hard time for her: it was in the middle of the Dictatorship. We struck up a friendship, we called each other several times by phone and I was even able to record her for an interview that was broadcast on my program on Radio Nacional Bariloche, which is chapter four of the book. It was a very deep interview; she was coming from her last tour in the South. And that was documented in the book.

What was Aimé's childhood like?

Aimé's parents had a very special relationship because they married when her mother, Gertrudis Reguera, was very young. She was thirteen, fourteen years old.

They had four children; one died. Aimé is the third. The youngest brother is the only one still living, in Chimpay. After having the children, the mother abandons the father. He is left alone with them. At that time, Evita Perón had opened some homes for orphans from the interior. Aimé was taken to live there; she was taken away from her father's side and ended up in a home in Mar del Plata. She grows up as an orphan, as someone who has no parents, who has no identity, educated by the nuns at school.

But her life is turned upside down because since she was a little girl she has had this wonderful musical talent that leads her to join the school choir at the age of seven. A couple from Mar del Plata heard her singing and decided to adopt her. They moved her to another school, keeping her as a pupil, but already with a musical guide. She always said that her tutors wanted her to dedicate herself to classical music. When she became independent, she left Mar del Plata, went to Buenos Aires, tried to survive as best she could, and joined the National Polyphonic Choir.

What did it mean for her to join the National Polyphonic Orchestra?

It was something wonderful because she lived a very lonely childhood. She recovers her family and her culture as a reverse process: little by little, studying, traveling, and talking to her grandmothers. She became a specialist of her own culture by doing fieldwork, recording the grandmothers. While she was a member of the national choir, she had a kind of epiphany when she heard the native peoples of Latin America perform the songs of their own culture. However, in the Polifónico he played classical music distant from his roots. There he said enough was enough and began to dedicate himself to Mapuche singing. Nobody did it, nobody sang in that language and nobody went on television or made press releases talking about the Mapuche theme.

What were her concerts like?

In the beginning, she accompanied herself only with the guitar and did folk songs until she stopped doing it completely. Then she dedicated herself to doing recitals with a compilation of "tahils", ceremonial songs, which she recorded from the grandmothers from whom she asked permission. Her concerts were true anthropology classes because she would tell you each one of the anecdotes with those grandmothers and she did it with such love that you ended up loving them.

Aimé decided to turn to the Mapuche repertoire in the middle of the military dictatorship. What was her response?

It is true that amid the military dictatorship she began to talk about issues that were already taken for granted, let's say. What happened with the Desert Campaign is something very simple: history is written by those who win. In all the school textbooks the indigenous people appeared as "malones", as the bad guys, as the dangerous ones. After the campaign, the surviving women were sent as domestic servants to Buenos Aires, families were separated, children were taken away to be adopted or raised as slaves for servitude. The same happened with the men they sent to the estancias. Aimé points out in the book: "uprooting is one of the things we have suffered the most".

During the Dictatorship, Aimé did not have a good time, but she was not directly persecuted because for the military the indigenous people were no longer a problem. The textbooks spoke about them in the past tense. Aimé said "Enough of saying that the Mapuches ate, dressed, lived. The Mapuches are here". And the same thing happened with the other peoples. But for the Dictatorship at that time the enemy was another one because it was also the Dictatorship alone. She once appeared on Mirtha Legrand's program dressed in traditional costume when Mapuche women did not wear anything that could reflect their culture.

What is the difference between the social context in which Aimé lived and the current one?

I have just put together a new chapter to show the difference in the historical social context called "What Aimé did not see". There I explain what is happening now with the culture. In 1992 the Mapuche flag was created and with the liberation of the dollar and the one-for-one, many foreigners came to buy land in the south. This made the young people rise to fight for their territory. All this Aimé did not see there. She would be very happy that the young people return to their identity, that they recognize themselves as indigenous, as Mapuche and that they try to help their community.

And between the context of the first book and the new version?

The environment has changed a lot because during the years of the Macri government two victims shook all the Mapuche communities: Santiago Maldonado and Rafael Nahuel. That increased discrimination and racism once again. It was precisely the younger generations who went out to try to recover their grandparents' lands.

She spoke to the children. Aimé's legacy is one of absolute dignity. When I traveled to Esquel to present the book, for example, -she used to go to Lago Rosario a lot where there is a Mapuche community- a tall man came up to me and told me that he heard her in his school, that he never forgot it and that now he was working for his community. Besides being very beautiful, Aimé had a very tender and direct way of communicating. She said that now the struggle had to be through culture; "the white man does not respect us because he does not know us".

All photographs are courtesy of Cristina Rafanelli and can be found in her book "Aimé Painé. La Voz del Pueblo Mapuche". Source: Argentina.gob.ar