How Pancho Villa Turned to the Pen in Lecumberri Prison

Villa's time in the bleak Lecumberri Prison—known as the “Black Palace”—could have been a dark chapter lost in the annals of history. But it turned into a transformative period for the legendary revolutionary. On the brink of execution, Villa found an unexpected ally behind bars.

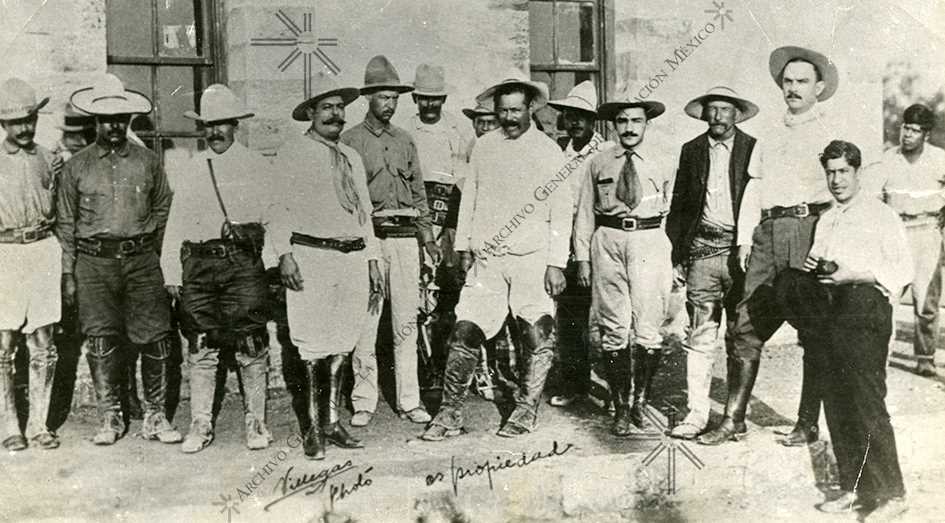

When we think of Pancho Villa, the flamboyant Mexican revolutionary general, we often picture a man on horseback, leading his troops through the rugged terrains of Northern Mexico. Known as the “Centaur of the North,” Villa's larger-than-life persona frequently overshadows the lesser-known chapters of his turbulent life.

One such period is his controversial imprisonment in Lecumberri Prison in 1912. Beneath the legend lies a more nuanced story—of false accusations, his time behind bars, and the remarkable legal efforts that aimed to set him free. Let's dive in, shall we?