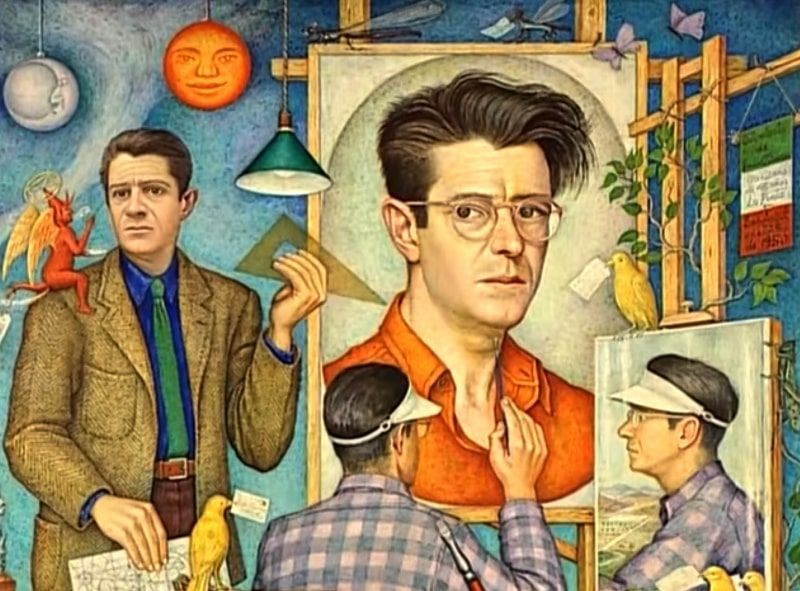

The artistic heritage of Mexican architect and painter Juan O'Gorman

With his work "The Historical Representation of Culture" Juan O'Gorman defined the landscape of Ciudad Universitaria. In libraries, schools, and public murals are part of the artistic heritage of Mexican architect and painter Juan O'Gorman.