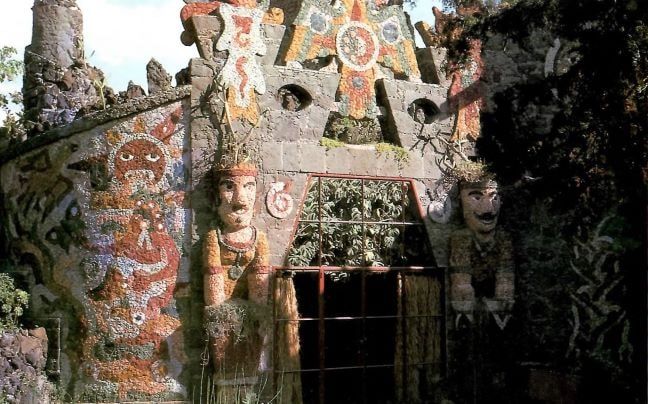

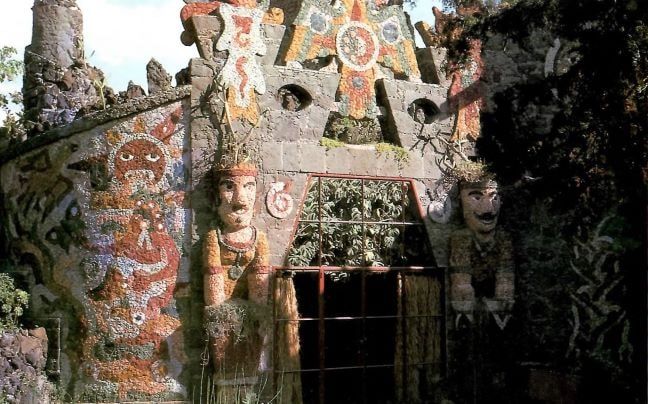

The memory of Juan O'Gorman's Cave-House

Juan O'Gorman's legacy is fundamental in the history of architecture in Mexico. Find out more about it by reading here.

Juan O'Gorman's legacy is fundamental in the history of architecture in Mexico. Find out more about it by reading here.

Calakmul Biosphere Reserve faces severe water scarcity due to climate change and human impact. Research reveals water body loss and animal suffering but also successful restoration efforts.

Deputy proposes stricter driver assessments for federal motor transport vehicles in Mexico. Mandatory theoretical and practical exams, along with regular training, are sought. The aim is to reduce road accidents caused by driver error, aligning with national road safety goals.

Mexico grapples with recurring droughts, even rain won't instantly end them. Droughts cause billions in damages and understanding them is key.

Mexico's archery team shines at Paris 2024 Olympics. The women's team secures third place, advancing to the quarterfinals. Alejandra Valencia leads with a strong performance. The men's team qualifies for round of 16. Matías Grande and Valencia aim for mixed team podium.