Wixárika, a people in communication with nature

Discover some elements of a complex and fascinating Wixárika world in which everything is related, in which everything and everyone is in communication.

The Wixárika people are original indigenous people who have lived for hundreds and hundreds of years in what we now know as the national territory of Mexico. The original peoples had already been living here for centuries when the Spanish first arrived on this continent.

Other original indigenous peoples are the Nahuatl, Tseltal, P'urhépecha, Mixe, Rarámuri, Pai Pai or Totonaco, for example. In contemporary Mexico, there are more than 60 different native indigenous peoples. Each of these peoples has its language, history, culture, landscapes, and its ways of relating to work and nature, to members of its group, and to members of other groups that, like them, form part of what we know as a national society or Mexican society.

The Wixárika people live in their ancestral territory, in the Sierra Madre Occidental, a wide geographical space located in the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and Durango. There is also Wirikuta, one of the main sacred places of the Wixárika people, which is located in the state of San Luis Potosí.

Its territory is varied. Some communities live at the top of the Sierra, surrounded by majestic peaks, cliffs, and rocks; others live in deep ravines or on the banks of rivers, and still, others live in coastal regions with temperate or warm climates. The Wixaritari (plural of Wixárika) are sometimes mistakenly called Huichols.

The word huichol means "the one who runs away" and they do not run away. The term wixárika means "person with a deep heart who loves knowledge". This is the true name of the Wixárika people.

Relations

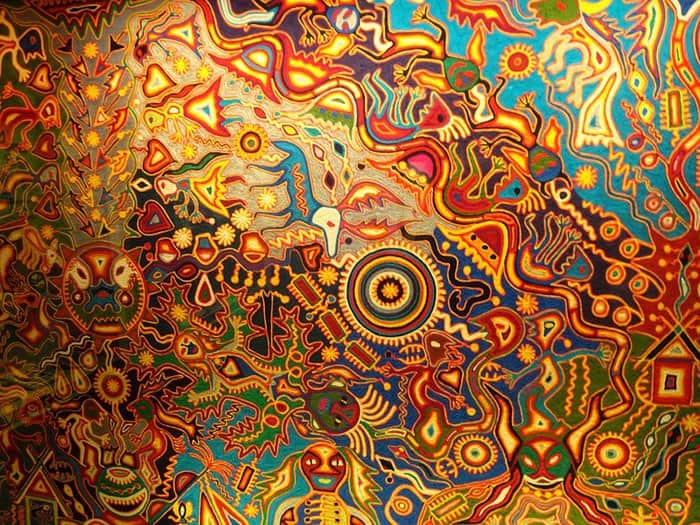

All people, plants, animals, the sun, air, water, earth, wind, oxygen, rivers and seas, caves, mountains, and deep ravines, all together are part of the same universe. We all share the same world, our world; in which everything is related to everything, some links unite us to each other and, at the same time, all of us to everyone.

Biologists, ecologists, sociologists, economists, and historians know this. So do the members of the Wixárika people. The Wixárika people know that the sun, the earth, the wind, the clouds, the water, and the seed are related to the cornfield, work, food, joy, and community ties. The Wixárika people also know that winter, drought, and cold are related to austerity, reflection, song, dance, pilgrimage, and waiting.

The Gods

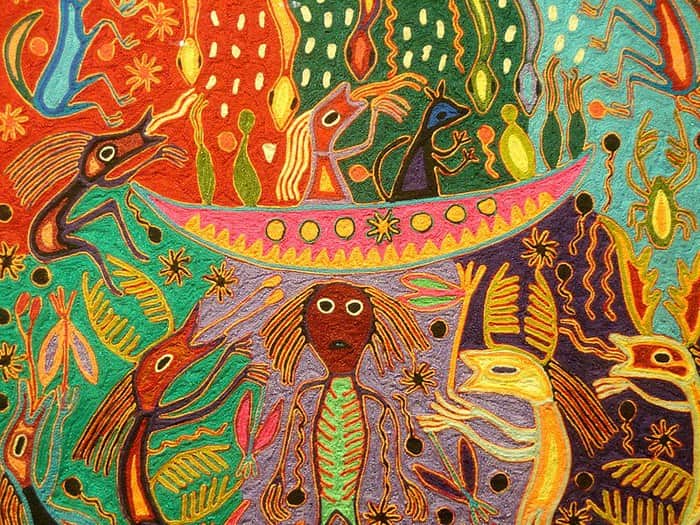

In each of the elements of nature, the Wixaritari have a god and they especially love each of their gods. The Wixaritari think of their gods as family.

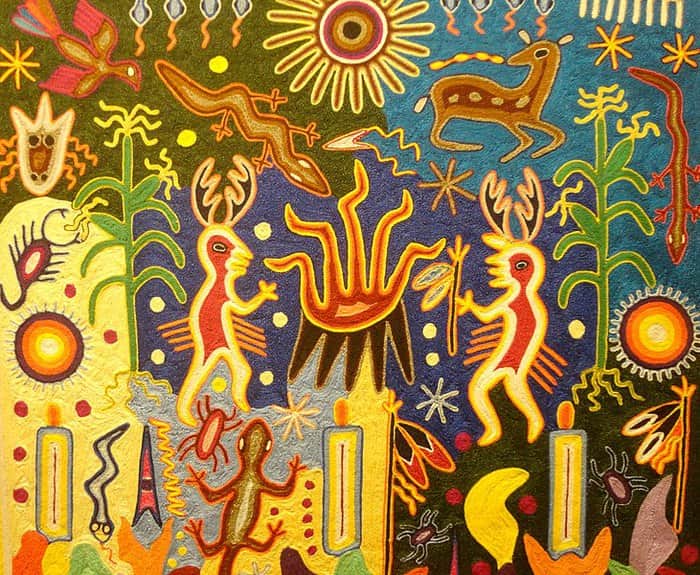

Tatewarí, the fire grandfather.

Nakawé, the mother water, the mother of all gods.

Yurienaka, the mother earth.

Otwanaka, the mother corn.

Ereno, the Moon, the goddess of love.

Kumatame, the god of the song and father of the corn.

Tayeupa or Tau, the father Sun.

Tamátsimáxakwaxí, the brother deer, a friend of the Sun, the dearest good, the one who knows more.

For the Wixaritari, the gods are part of their families, they are their ancestors, they are very dear beings who deserve veneration and, at the same time, they deserve company, conversation, celebration, and gifts.

Communication

Therefore, because the gods of nature that are the ancestors need company, conversation, parties, and gifts, the Wixaritari have designed a complex, creative and delicate system that allows them to get in touch with their gods to invite them to talk, to recognize before them their faults and ask for forgiveness, to ask them for explanations, to tell them about their problems and ask for support, to introduce them to the new children who are born, to listen to what they have to teach them from their ancestral wisdom, to ask for advice on the appointment of their rulers, or to sing and dance with them in endless nights.

In this way, the Wixaritari and their gods are part of the same people and the same world. Thanks to this system of communication, the gods and the ancestors are present in the ceremonies of birth and death, in the organization of work, in the dawns, and the harvests. They appear with the rain, run with the deer, emerge among the sea foam and beat in the very heart of the fire that the families always keep burning, taking care among all that it never goes out.

The Wixaritari know that, in nature, it is necessary to keep alive the ties that unite us all with everyone, to keep the contacts strong, to ask others how they have been and what they need, to let others know how we are and what we need. And this also refers to the air, the water, the earth, the plants, and animals that are part of ourselves by forming, like us, part of nature, of our nature that belongs to everyone. The Wixaritari know that in this way, in communication, we can all be better, feel accompanied, and know that we are part of a world of our own to which we belong.

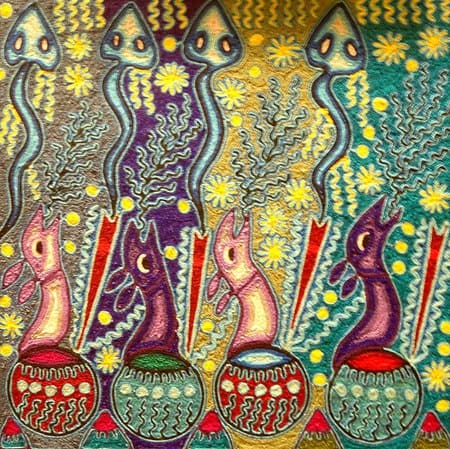

El Niérika

This complex, creative and delicate communication system developed by the Wixárika people is called niérika. The Wixaritari gods are the very embodiment of all the elements of nature, which is why the Niérika allows people to communicate with the gods and, at the same time, with their ancestors.

Niérika is a system that allows the Wixaritari to come into contact with life itself, with their ancestors, with the history of their people, and, in a complex and rich way, with all the wisdom accumulated in the universe. Because, if there is something that the Wixaritari value, it is knowledge.

The Niérika is both a threshold and a window. It is a kind of limit or frontier that, at the same time, separates things and puts them in contact. It is like a subtle veil, almost imperceptible. Through the niérika, the Wixaritari look out on the world of the gods, the same world of their ancestors, and the gods look out on the world of people and nature. Like all frontiers, the Niérika has transit of going and returning.

The Niérika allows the Wixaritari to bring order to their daily lives and live in unity with an otherwise chaotic and unpredictable world. It also allows them to relate the present with the past and, for this very reason, it allows them to live with an awareness of their history and to know that they are the subjects who will design their future.

The instruments of the Niérika

To think of Niérika is to think of the world and of life itself, of complexity, diversity, and relationships. It is to become aware that we all relate and belong to a world that is bigger than ourselves. There is a wide and diverse set of instruments that allows the operation of this complex and creative system of communication, learning, and reflection that is the niérika.

Each of the instruments of the niérika must have an orifice in the center because it is through this orifice that communication with the other worlds is established. In a real or symbolic way, in the center of the niérika, one must see the presence of emptiness, the presence of nothingness. The Sun, the face painting, or the wrapping dance are also instruments of the niérika. Some of these instruments are introduced briefly next.

The Sun

It's the big look. It's the immense look. It is the open window that allows the gods to look out on the Earth to see the people who are their beloved daughters and sons. To this great and heavenly gaze, people respond by painting their faces with the color of the Sun, embroidering circles on their clothes, or opening windows in their homes. Because they want communication to be horizontal and reciprocal, back and forth. The color of the Sun is a sacred color.

El Peyote

The gods, in their generosity, wanted to show people the best structure of the instruments of the Niérika. Then they created the hi'ikuri (peyote), small cactus with a dark center that appears on the earth as if it were an eye.

Peyote is one of the main instruments of the niérika. Thanks to it, priests talk directly with the gods during their dreams and when they sing. The gods instruct the priests through peyote, advise them to make decisions, and tell them the history of the Wixárika people so that they can repeat it later in their ceremonies and festivities. For this reason, some consider peyote to be the equivalent of a book in which all knowledge resides.

Face painting

Just as the Sun rises in the morning and rises through the celestial curvature, so the Wixaritari paints their faces, following lines that look like true curved and spiral paths. They use the sacred yellow color that they extract from a root (uxa in wixárika) and trace lines that move in a spiral and come out of a center. In this way, the cheeks and faces themselves become niérika.

The mirror and the face

The mirror is a special Niérika because it reflects the face of people and also the face of the world. Faces are part of Niérika's instruments because they are windows of communication and linkage.

If you look carefully, through the face you can see the essence of people, their real nature, their human quality, their heart, and the deepest feelings that people keep. Nature also has its face and mirrors reflect it along with water surfaces when they are calm.

The dance of the entanglement

Another instrument of the niérika is also opened through the dance of the entanglement. This dance opens a niérika in the middle of the communities and, at the same time, draws and establishes a sacred territory.

In this enveloping dance, everyone makes a line and follows the pointer that guides them through a space that, thanks to the dance, becomes a ritual space. The pointer guides everyone so that, with their dance, they trace a kind of snail on the surface of the earth, in search of a center.

When they reach the center, the dancers begin the exit route, thus strengthening the traced spiral. These two movements, of entrance and exit, are repeated throughout the whole night and are accompanied by the wixaric voice of the singer and the music of the drum, the violin, the rattle, and the guitar.

The coamil well

Also on earth the nierikate (plural of niérika) are necessary. Otherwise, how could the gods participate in the processes of sowing, growing, flourishing, and harvesting? Among the Wixaritari, the milpa is called coamil and coamil is to work in the milpa.

So, when a community is ready for coamilar, to begin the planting in the coamil, they all go together, men and women, girls and boys, to the center of the field, and there they dig a well in the manner of a niérika. Inside this well and in the middle of ritual ceremonies, they place offerings that they then cover with earth.

In this way, they ask the gods for their attention and support during the whole process of the corn. The gods then summon the clouds that bring the rain, watch over the sprouting of the plants, keep away the animals that damage the corn, and concentrate the light and heat of the sun so that they mature and dry the cobs soon.

Eyes on the house

The family houses are old. They remain in the same place for years and centuries. Each Wixárika house belongs to the families that inhabit it and also to the deceased who lived in it. That is why it is necessary to establish communication points that allow the ancestors to enter and leave their houses: to be in them because they feel comfortable there and to visit their descendants.

To do this, and so that the gods may appear, the Wixaritari open circular holes in the walls of their houses and, sometimes, paint them. This way, when they peep out, the gods and the ancestors can know that there are sick people at home, that a girl or a boy was born, that the reserves of corn for the winter are running out, or that the people that constitute the families are remembering them.

The stone disks

The tepari are disks carved in volcanic stone that are then decorated with various images. This is how they work: in the center of all Wixaritari temples, there is always fire lit, which is the point where all Wixaritari meetings converge. Under this fire, there is a well that establishes communication between the underworld, the world of people, and the underworld or world of the 39 gods.

This well is a powerful center of cosmic communication. But since the forces of evil reside in the underworld and these forces are always trying to penetrate the other two worlds, the Wixaritari place a sacred tepari that closes all possibility of entry and keeps them captive in their underworld.

The tepari have different images on their two faces: on one, which is placed downwards, they have drawings representing the beings of the underworld; on the other, which is placed upwards, they have drawings representing the Sun and other protective gods. The tepari are sacred. They also have other illustrations that express the complex relationship that many of the elements of nature have. For that reason, the tepari are considered the material for reading.

These disks are also placed on the altars of the temples and in the sanctuaries of the mount that the wixaritari establish to communicate with their gods throughout the daily tasks. They establish these sanctuaries in special sites such as rocks, caves, water eyes, or feet of a tree. The tepari are in themselves a kind of tabernacle.

The arrows

When placed vertically on the earth, besides representing the axis of the universe, the reed arrows (muwieri in Wixárika) establish a communication channel, an open tunnel between the earth and the sky. The arrows are therefore ceremonial instruments of priests, singers, and traditional doctors.

When the Wixaritari wants to send specific messages to their gods, they place small symbolic objects on the arrows. Each object means something different: an embroidered cloth is a request made by the embroiderers to sell their products well; a twisted rope asks for success in the hunt; a miniature violin or guitar are prayers that ask for musical talent, a good voice or skill; quartz crystals carry messages to dead relatives; sparrow feathers are a plea for health and protection from disease; blue magpie or parakeet feathers ask for good crops; eagle feathers establish a direct connection with the Sun, which is the morning star; and a bundle of tobacco is a good gift, a message of friendship to the gods.

Las jícaras

The jícaras (xucuri in wixárika) are dishes made with guajes. Like all Niérika, they have a center that is formed with diverse drawings made with paint or with chaquira glued on a wax base. These drawings leave an empty area in the center, an eye, a symbolic hole. The images that appear more frequently in the jícaras are those of the Sun, the corn, the peyote, the eagle, the snake, the scorpion, or the deer.

On the jícaras are placed the prayers and also the gifts that people address to the gods. The priests use these jícaras to give drinks to the gods during the ritual ceremonies and, after offering the drink to the gods, they also use them to give drinks to those who participate in the ceremonial festivities.

The candles

A candle (katira in wixárika) is a niérika. It is a niérika because of its cylindrical shape which, like the arrow, brings together the different levels of the world. The candles are the pillars of the world and support the vault of the sky. That is why it is important to keep many candles lit at all times.

Further, with their light, candles help the Sun to rise every morning, mark the way and give encouragement. Candles are part of the Niérika because they illuminate the darkness that characterizes the hereafter and enable people to enter the world of their ancestors, to visit them, to summon them, and to chat with them.

The Eye of God

The eye of god (tsik+ri in wixárika) is a very important niérika. It is constituted by a tangle of stamens that, having as support a cross of sticks, turn in a concentric way around a void, an eye, an absence of matter.

Moving around the center, the stamen forms rhombuses. Each rhombus is prepared with a different color and the tsik+ri can have rhombuses of up to five colors. There is a very interesting Wixárika legend.

The story tells that Kauyumarie, one of the gods responsible for the creation, was very worried because he didn't know what he had to create. He did not imagine how the world he had to create could be. So he had an idea, took a tsik+ri, and peeked through it to spy on the world in its entirety. And he had no problem, through this eye he saw everything he needed to create with signs and details. Because it is important to know that the tsik+ri allows him to see the unknown.

When children are born in the communities, a presentation ceremony is organized so that the gods know them and take them into account. In this ceremony, the priest holds a tsik+ri over the head of each child who, at the same time, makes a big noise with rattles that they have in their hands.

With this noise they call the attention of the gods towards their people and, once attracted, the gods appear through the tsik+ri to meet them. This ceremony takes place once a year from birth and for five years in a row. In this way, presentations are made and communication is established between the old gods and the new wixaritari who are born.

Finally, at the end

It is difficult to say goodbye to the Wixárika world. Among other reasons is because it is a world full of knowledge, history, creativity, patience, shared life, and longing. Also because it is a world that tells us new things, things that few have heard before, and also tells us things that we already knew but that we reconstruct when we learn to see them from other points of view, from other principles, and with other metaphors.

Instead of ending up with conclusions that we obviously could not reach when talking about a complex world that is constantly transforming, while at the same time remaining, we propose to end up simply remembering that, as the Wixárika people teach us, the world is rich, abundant, complex and open to movement.

Let's finish by saying goodbye to that reality in which the deer is a big, agile, and light god that turns into peyote, into corn, into the sun, and again into deer, and always remains a close and loving friend of all people.

The clouds that bring and carry the rain at their pleasure. Or of the earth that feeds and welcomes the seed as only mothers can do. Let us speak of the rocks and boulders that hold dormant the souls of the ancestors, and of the mountains that, as the story goes, were born at the end of the flood from a forgotten branch.

Let's talk about the Sun, the morning star and its friend the eagle, about the sea foam and the beautiful song of Kumatame, which with its voice calms down beasts and storms. The water and the swallow that symbolize it, and also the white dove, are in charge of taking care of the water (that's why nobody should kill the white doves).

So, after talking about this and more, the relationship, the links, the conversations, the prayers, the offerings, the explanations, the visits, the stories, the rites, the prayers, the music, and the dance that allow the Wixárika people to constitute themselves in their traditional life and their contemporary life as a people aware of complexity and movement, aware of transformation and change.

In the beautiful example offered by these people with their ancestral culture and their unwavering loyalty, let us look for the possibility of giving new meaning and sense to what we now know as communication between people and with nature.

Author: Luz Chapela, Source: Library of Official Publications of the Government of the Republic. The texts constitute creations derived from ancestral archetypes that live in the oral narratives of the people and communities that make up the Xixárika people. The reproduction, in part or whole, of this work, is authorized provided that the source is cited, whether for educational purposes or non-profit purposes.