History of the Inquisition in the world

The Inquisition was a tribunal created in 1231 by Gregory IX to inquire or investigate cases of heresy. Its objective was the reconciliation of the heretic with the Church and, in this way, to achieve eternal salvation. To understand what the Inquisition was, we must begin with its origin.

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition has been one of the most debated and misunderstood institutions of all times. Interests in a political, if not religious, nature have given rise to a series of prejudices that prevent a clear and objective image of this institution from being obtained.

To analyze this institution, we must always bear in mind that it was the fruit of an era in which intolerance - political, religious, etc. - was the common denominator not only in Spain and its colonies but also in Protestant and Muslim countries. In this context, the Inquisition was one of how intolerance was institutionalized.

The reader who is beginning to learn about the subject must differentiate between two institutions that, beyond their similarities, are different: the medieval Inquisition and the Spanish Inquisition. Both were due to different causes, possessing different attributions and procedures. One of the main differences is the mixed character -state and ecclesiastical- of the latter, which implied its dependence on the crown.

The Medieval Inquisition

The Inquisition slowly emerged as an instrument destined to defend the faith and society threatened by the action of heretics. Heresy is by definition the error in matters of faith held with pertinacity. The Church saw in the heretics a danger for its existence and, above all, for the salvation of the souls of believers, who could be confused with their teachings.

The heretics were an attack against the Church, the State, public order, and the constituted authorities. Consequently, the real scope of the crime of heresy is explained not only by strictly theological factors but also by political, social, juridical, and economic factors; without this consideration, we would not have a clear vision of its significance.

From the beginnings of Christianity, the first heretical groups appeared. Some claimed that the Jewish law was necessary for the salvation of souls; others attributed to the Second Person of the Holy Trinity only a divine character inferior to that of God the Father (Subordinationists) or a divinity by adoption (Adoptionists); some did not distinguish the Persons of the Holy Trinity, seeing in them only different modes of the same divinity (Modalists).

The Gnostics, for their part, constituted another form of heresy: they claimed to possess profound knowledge inaccessible to the common people. In their turn, the supporters of Montano claimed the imminence of the coming of Christ and prepared for it; the millenarians maintained that between the end of the world and the final judgment, our Lord Jesus Christ would return to Earth to spend a thousand years with the chosen ones.

During the fourth and fifth centuries, new heresies disturbed the tranquility of the Church and Christian society. Two of them centered their attacks on the Holy Trinity (Arianism and Macedonism); while others focused their attacks on the incarnation of Christ (the Pelagianism and the Semi-Pelagianism).

At the end of the 12th century, two new groups of particularly violent heretics emerged in Europe: Cathars and Waldenses. The Cathars rejected Catholic rites and sacraments, devoting their greatest efforts to anti-Catholic preaching and practice, which included numerous acts of bloodshed; among them, the assassination of the papal nuncio. As for the Waldenses, the initiator of their movement was Peter Valdo, a wealthy merchant from Lyon who, after having the Gospels translated, sought to live according to their teachings: he sold his goods, left his family, and dedicated himself to preaching (1170).

His disciples were also known as the poor of Lyon. The Waldenses maintained the right of women and laymen to preach; they denied the value of the mass, offerings, and prayers for the dead; some even disputed the existence of purgatory and preached the ineffectiveness of going to pray in the temples. Apparently, by their attacks on the properties of the Church, they attracted the favorable opinion of many people, managing to expand throughout Europe.

The initial repression of the heretics was in charge of the civil power, which was threatened by the instability generated by the revolts. For this reason the lay authorities, before the existence of the Inquisition, in the application of the norms of Roman Law, provided for the penalty of burning at the stake, because heresy was considered a crime against God and the State and should be punished with the same rigorousness as other crimes of lese-majesty.

Given the rapid expansion achieved by the Albigensians and, to a lesser degree, by the Waldenses, it was necessary to standardize the legislation of the different Christian kingdoms, for which various authorities requested the support of the pontiffs. At the Council of Verona (1184), Lucius III ordered the bishops to carry out inquisitions in places where the presence of heretics was suspected.

Thus the Tribunal of the Faith was named. But this was not enough. Innocent III made remarkable efforts, with the support of Catholic monarchs and nobles, to paternally call the heretics to repentance; when these attempts failed, a crusade was called against them (1209-1229). The military victory of the Catholic armies was consolidated by inquisitorial action.

In most of Western Europe, inquisitorial tribunals were set up under the respective bishops. The tireless activity carried out by the Order of Friars Preachers (the Dominicans) against heretics, as well as the better preparation of its members and their international organization -which escaped the territorial limitations of the dioceses- led to the delegation of most of the inquisitorial tasks to them.

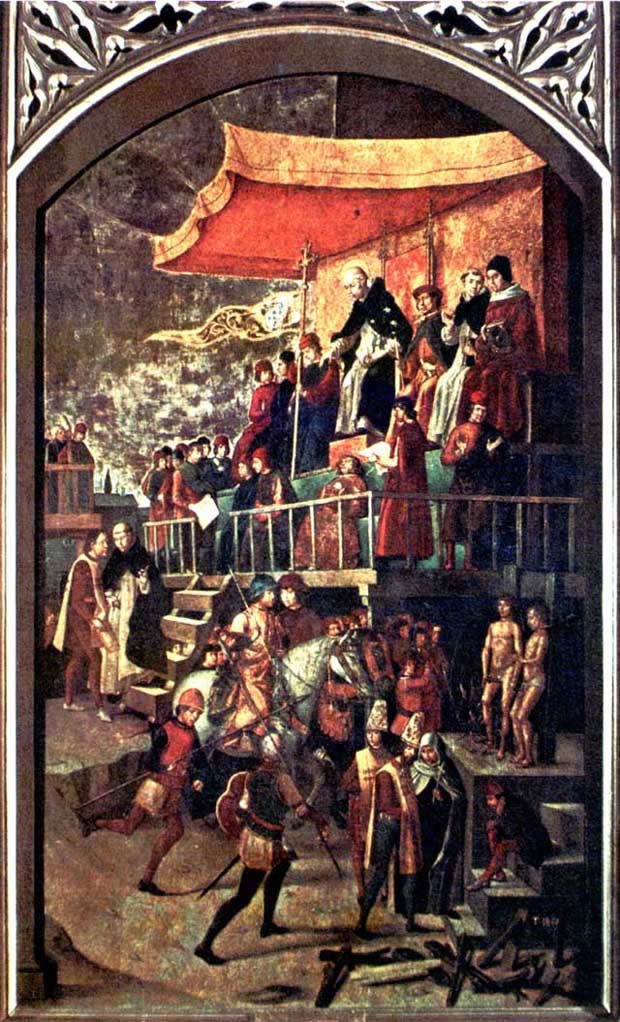

Originally, the Inquisition was not a permanent tribunal; it was rather an attribution of the bishops within the scope of their dioceses; however, the overload of their work prevented them from dedicating themselves to such tasks. For this reason, the popes appointed pontifical inquisitors who exercised their functions in the face of indications of the existence of groups of heretics for a certain area.

Before acting, they published an edict of grace - a kind of general pardon - that granted pardon to all those who voluntarily presented themselves to confess their faults and repented of their heretical conduct. Once the term expired, the respective processes began to be carried out. The inquisitors were only responsible for the application of spiritual sanctions, such as the recitation of prayers, fasting, ordering the placing of holy symbols, and, worst of all, the excommunication of the obstinate. The latter was handed over to the civil authorities so that they could apply the sanctions ordered by the respective monarchs: confiscation of their goods and burning at the stake. Few people were condemned to the latter sanction.

At the time, the foundation of society and the State was religion, which was the basis of the political and legal order. In a society that prided itself on being Christian, where Revelation had a divine character, this became the fundamental social law, the violation of which was a serious crime. In a Catholic state, the prince was obliged to protect the one true religion. From this obligation flowed the right to issue penal laws against those who disturbed religious order and unity, and therefore public order.

As a consequence of this intertwining of religious and political motivations, the struggles between Catholics and heretics took place in both fields -against the Church and the established authorities- constituting, in fact, not only subversive acts but true civil wars. It is worth noting that at the time, it was normal for the laity to be more rigid than the clergy in punishing heretics since they were repudiated by the common people. In turn, the pope was much more lenient than the local clergy, who were often urged by the faithful to greater rigor.

The organization of the medieval Inquisition was not the work of a single pope but the result of a long process, initiated during the administration of Lucius III, continued during the pontificate of Innocent III and culminated by Gregory IX who, through three different bulls - between 1231 and 1233 - gave it its definitive structure. The Inquisition was, like most of the institutions of the Middle Ages, the product of a practice that was initially restricted and then gradually extended and perfected.

The Spanish Inquisition

Current Spain, at the beginning of the 8th century, was made up of the Visigothic peoples, mostly Catholic and, also, of diverse religious groups, among which the presence of the largest Jewish community in the world is worth mentioning. These peoples coexisted amid recognized religious freedom, with no more limitations than some sporadic incidents.

As is well known, the year 711 saw the Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula. This invasion had, at the same time, a religious, political, social, and economic character. The conquest, dogmatism, intolerance, fanaticism, and abuses of the Muslims gave rise to religious hatred and intolerance.

The Catholics, for their part, did not renounce their faith, took refuge in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, in the so-called Kingdom of Asturias, and from there confronted the Muslim invaders in a long and bloody war that, with intervals of peace, lasted from the year 711 until 1492, when, with the capture of the city of Granada, the last Moorish stronghold in Spain fell.

It is easy to understand that religious intolerance was the common denominator of the time, that each person saw in others of different beliefs an enemy of God and of the King, with whom he was in a constant struggle for survival and absolute dominion of the territories.

Causes

Having briefly explained the complex web that was woven in this period, overcoming unilateral simplisms, we can add among the main causes the following:

The "Jewish threat"

The most important cause that directly motivated the creation of the Hispanic Tribunal was the so-called "Jewish threat". The serious economic crises that shook Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries, to which contributed the plagues and epidemics that originated an unprecedented demographic fall, led to the massive impoverishment of the population and economic restrictions of the crown.

During the crisis, the only ones who consolidated their economic positions were the moneylenders and the lessees of the royal tribute trade virtually monopolized by the Jews. They had practically become the masters of Hispanic finances. One of the reasons for such a situation was the fact that loans with interest were considered morally questionable for being incurred in the sin of usury, while the Jews considered them perfectly licit.

They were questioned for their administration of the collection of royal taxes - a job that was not very well understood at all times - and they were held responsible for their lack of transparency in the management of the charges imposed by the sovereigns. As if that were not enough, the Jews were seen as a State within the State because, before being good and loyal subjects of the crown, they were, above all, Jews: a nation without a territory and, therefore, in search of one of their own.

These reasons and religious differences fueled anti-Semitism, which thus emerged as an expression of animosity towards a bourgeoisie that grew rich amid widespread poverty, resentment towards dishonest tax collectors, and hatred of usurers. In this context, some various anti-Jewish events and protests blamed all the evils of the time on the benevolence of the authorities towards the "deicidal people" for which God supposedly punished the population.

For their part, the Jews also staged some bloody events against the Catholics, which contributed to exacerbating tempers. Additionally, to move up the social pyramid and achieve positions reserved for Catholics or to avoid the prejudices and restrictions against them, many Jews falsely converted to Christianity by receiving baptism and participating externally in its cult while, privately and almost publicly, they continued with their previous religious practices.

This dual behavior earned the wrath of the true Christians who saw the Judeo-Converts reaching the highest dignities and positions in society, the State and the Church itself - becoming a kind of infiltrators - to conquer power and impose their religion and their political, social, and economic organization for their benefit.

When the Inquisition was established, during the first years of its existence, it was mainly in charge of controlling the Judeo-converts, since, for someone to be prosecuted, he had to have freely and voluntarily become a Catholic. However, the situation of the converts became complicated because they were pressured by their Jewish relatives and friends to return to their former religion and, in doing so, they incurred apostasy and, therefore, were subject to the control of the Inquisition.

After all the attempts of the monarchs to assimilate the Jews peacefully failed, they ended up decreeing the expulsion of all those who did not convert to Christianity. By that time - for a long time before - anti-Semitism was a common sentiment in most of Europe. Thus, before Spain, the Jews had been expelled from England, France, and other kingdoms; in addition, they had been victims of cruel massacres and persecutions in Germany.

The assertion of royal power and the emergence of Spain

In the Middle Ages, the origin and sustenance of political power were explained as a direct consequence of divine will. Religion was the sustenance of society and the state, morality was the basis of the legal order. Religious struggles were often fueled by political struggles. The Catholic authorities saw in every Muslim or Jew, not only a man of another religion but also a potential conspirator against their power, against the regime and its foundations, against social peace and public tranquility; therefore, a political enemy.

This doctrinal assumption was confirmed by historical facts: the invasion and the continuous attacks of the Muslims; the alliances between them and the Jews against the Catholic Monarchs; the support of the Moors to the Muslim attacks against the coasts of Andalusia; the conspiracies of the Moors to propitiate a Turkish invasion to the Iberian Peninsula, etc.

During the reconquest in the Iberian Peninsula, two great Catholic kingdoms were formed: Castile and Aragon. Isabella of Castile married Ferdinand, crown prince of Aragon; five years later, Isabella became Queen of Castile and, in the same period, Ferdinand was crowned King of Aragon.

Their marriage did not lead to the unification of Spain because both kingdoms remained independent of each other. Isabella and Ferdinand conceived the project of centralizing in them the political power, previously dispersed in the nobility, leading, in the end, to the union of their crowns in a single State.

Among their first measures, they proceeded to create five royal councils, one of which was the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition. This was the first institution that, with a single common head -the General Inquisitor- for both kingdoms, had under its power all of Spain and its colonies. Thus, the kings used spiritual unification with a clear political purpose: Spanish unity.

Thus Spain was born, forged in the millenary struggle against the infidels, consolidated in the struggles against the Judaizers, nourished in the wars with the Protestants, confirmed in the vast task of evangelizing a whole new world; a bastion of the Catholic Faith; always a defender of Christianity and fidelity to the Church, always devout.

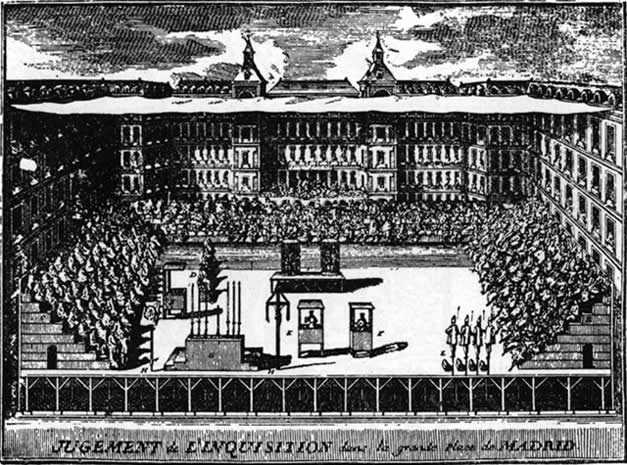

Creation

The Spanish Inquisition was created, previous authorization of Pope Sixtus IV, by the Catholic Kings in 1478. Two years later it began its actions in the city of Seville to later expand throughout the rest of Spain and its colonies. At that time, the Spanish monarchy, to centralize and organize its power, had five royal councils: Castile, Aragon, Treasury, State, and the Supreme and General Inquisition. The crown used the latter as an organism of social control, directing its efforts both to the defense of faith and public and private morality, as well as to the defense of loyalty to the monarchs and social peace.

Procedures

When a person was denounced before the Holy Office for a crime within its competence, it initiated the respective investigation. The Tribunal had jurisdiction over the following types of crimes:

Against faith and religion: heresy, apostasy, blasphemy, etc.

Against morals and good morals: bigamy, superstitions (witchcraft, divination, etc.).

Against the dignity of the priesthood and the sacred vows: saying Mass without being ordained; passing oneself off as a religious or priest without being one; soliciting sexual favors from devotees during the act of confession, etc.

Against the Holy Office: this category considered any activity that in any way impeded or hindered the work of the tribunal as well as those that attempted against its members.

The Tribunal also acted as a censor. While the civil authorities exercised censorship before the publication of any writing, the Inquisition exercised post-publication censorship. It did so in two ways: purgation or prohibition.

The complainant was asked to provide evidence or other testimonies to support his statements. If there were at least three made by honorable persons and who did not have any animosity against the denounced one, the process was initiated, for which they detained him. The denunciations were carefully reviewed by the inquisitors, who ordered complementary investigations.

Usually, they consulted the case with the qualifiers -sort of advisors that the Tribunal counted on- who played the role of the previous instance to the beginning of the inquisitorial process and their decision could lead to filing the file. In this case, the denunciation and the proceedings remained in a kind of indefinite suspension, which could be resolved in the future, in the event of a new denunciation or reiteration of the previous ones, as well as in the case of the presentation of additional evidence or testimony.

The raters were appointed from among experts in theological and juridical matters; generally, they were ecclesiastical authorities of the highest level, or professors specialized in the subject. Their opinion was taken as of great value but, in deciding, the criterion of the inquisitors prevailed. After the evidence was gathered, the accused was imprisoned and taken to the secret prisons of the Inquisition, where he was repeatedly asked to repent and confess the reason for his arrest.

He was held completely incommunicado and was not allowed any type of visits, not even from his closest relatives. The detainees were provided with an adequate food ration -superior to that of the common prisons of the time- which included meat, milk, fruit, and wine. If the defendant had economic resources, the value of his food was deducted from his assets, which were sequestered; otherwise, the cost was assumed by the Court.

The prisoner was required to keep total confidentiality of the events that took place during his stay in the inquisitorial facilities. His habitual isolation was only interrupted by the Tribunal officials who, from time to time, visited him to persuade him to confess his guilt.

The reason for the insistence on voluntary confession was that the Tribunal did not seek the heretic's punishment but his salvation. For this, the repentance of the accused was fundamental, which would be manifested in his predisposition to confess the facts that had given rise to the process.

In the cases in which the defendants were self-incriminating, the sanctions were usually benign; in the majority of such cases the actions would culminate in the payment of a fine or in listening, dressed as a penitent, to mass in the main church; in making pilgrimages, saying some prayers, etc.

If there was evidence -among them at least three witnesses- but the defendant did not recognize the faults attributed to him or if he had committed perjury in his declarations, after having used all the possible mechanisms to obtain his confession without result, after previous warnings of the case, torment could be applied to him, in conformity with the procedures of the civil courts of the time.

The Tribunal had among its powers the ability to confiscate the property of the accused. The seizure of goods was ordered by the inquisitors at the beginning of the process, who, in the most serious cases - as long as the guilt of the defendant was demonstrated - could order their confiscation.

The money collected did not enter the patrimony of the Church but of the monarchy and was destined to finance the actions of the Tribunal itself. During the first years of its operation, the Spanish Inquisition had an enormous amount of resources but, at least since the 18th century, they were not enough to cover its expenses. This led it to resort constantly to the support of the crown.

The process was conducted in the greatest possible secrecy and both the accused, their accusers, and the officials and servants of the Holy Office themselves were obliged not to reveal anything of what happened. If they violated this prohibition, they were treated with a severity similar to that used with heretics.

This absolute secrecy of the inquisitorial procedures was one of the origins of the widespread black legend about the Holy Office since the population used to invent the most improbable stories about it, which were transmitted from generation to generation.

These tales were enriched by the additions made by each new narrator when he referred them to his most trusted friends or close relatives. People sought, through their conjectures, to understand the workings and purposes of such a mysterious Tribunal, before which they had seen some of their relatives and other personalities of the time appear.

The trials did not have a predetermined duration and consisted of a series of hearings to which the accused were subjected to determine their responsibilities. The accused were taken to the so-called courtroom, where they would meet the inquisitors and the prosecutor. The prosecutor would only accuse the suspect in generic terms, without specifying at any time facts or circumstances that would let him know the identity of his accusers.

This was done to avoid later reprisals against the witnesses. If the inquisitors considered necessary the use of instruments of torture for the clarification of the facts, if the counterclaims to the defendant to confess failed, they would order, using the respective sentence, his submission to the question of torment. Among the instruments of torture used by the Inquisition the main ones were:

The claw: consisted of holding the prisoner with his arms behind his back, utilizing a rope moved by a claw, and raising him slowly. When he was at a certain height, he was released abruptly, stopping him abruptly before he touched the ground. The pain produced at that moment was much greater than that caused by the ascent.

The rack: they placed the prisoner on a table, tying his limbs with ropes attached to a wheel. This, when turned little by little, stretched them in the opposite direction, causing terrible pain. At the time it was the most widely used instrument of torture in the world.

The water punishment: while the defendant was immobilized on a wooden table, a cloth or a rag was placed in his mouth, sliding it, in each case, to his throat. Then the executioner proceeded to pour water slowly, producing in the prisoner the sensation of drowning.

The person who used these instruments of torture was the executioner, a hired worker of the Tribunal. On numerous occasions, the same executioner from the civil courts was used. In addition to the executioner, only the inquisitors, the bailiffs, the notary, the doctor, and the defendant could enter the torture chamber. Contrary to what is generally believed, the Inquisition did not invent torture as part of the legal procedure, nor was it the only court to use it. Its use was generic to all courts of the time.

In this respect, we can maintain that it was more benign in its use than the civil courts because, unlike the former, it was only authorized in exceptional cases, the maximum duration of the torment was an hour and a quarter, it was forbidden to produce bloodshed or mutilation of any limb and the doctor together with the inquisitors themselves - to avoid abuses by the executioners - supervised its application.

The Spanish-American Inquisition

Despite being the same institution, the particularities of the Spanish-American colonies caused many differences with the functioning of the peninsular Holy Office. Among the most important, we must mention the exclusion from the inquisitorial jurisdiction of the majority of the population, as the indigenous masses were exempted from the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

The basic reasons were two: the first, that the native settlers were just being instructed in the Catholic religion and, for the most part, could not yet clearly understand the dogmas, much less distinguish them from heresies. The second, closely related to the previous one, is that the declared intention of the monarch was not that the Tribunal should be hated but loved and respected as it was the case in the Iberian Peninsula, for which reason he sought to set an example to the natives by controlling the conduct and doctrine of the Spaniards.

This unaccountability of the indigenous people meant that the Holy Office in America had an eminently urban character, while in the metropolis it was fundamentally rural. Let us remember that the Hispanic conquerors who came to these lands lived in the so-called "Spanish towns" for political reasons, in compliance with the orders issued by the civil authority. In these towns, the action of the Inquisition was concentrated, which only included the white, mestizo, or black minorities.

In addition to the aforementioned peculiarities of the Indian Inquisition, other distinctive features include the greater extension of the inquisitorial districts, their relative independence to the Supreme Council, and the typicity of the processes. Regarding the former, the jurisdictional delimitation was originally defined with those of the respective viceroyalties. This meant that each indigenous inquisitorial district reached millions of square kilometers in extension, a territorial amplitude that exceeded that of Spain by several times.

The latter was the result of the difficulties of communication with the Supreme Court, the central body of the Holy Office, despite which, in the few cases in which the accused were handed over to the secular branch, the prior ratification of the Council was required. Finally, the content of the processes favored the development of a very typical and peculiar subject matter, differentiated from that of the peninsula, as it took place in a different reality.

Causes of the extension of the Inquisition to the West Indies

The second half of the 16th century was quite complicated for Spain both internally and externally. The decade of the sixties saw the Moorish uprising of the Alpujarras, the pressure of the Huguenots on Catalonia, the rebellion of the Low Countries, the Turkish advance through the Mediterranean, the religious wars in France, the Anglican restoration, and the persecution against Catholics in England; also, the attacks of the Protestant pirates, the pontifical revision on the titles that legitimized the Hispanic domination in the Indies, etc.

The aforementioned conduct of the Holy See was because it considered that Spain had not fulfilled the evangelizing role to which it was committed and was manifested in documents such as the Bull In coena domini of 1568. To make the situation even more complicated, the Spanish American colonies, that is to say, the viceroyalties of Peru and Mexico, were in deep social unrest. In both, there had been rebellions of the encomenderos (conquistador landowners)with the consequent civil wars among the conquistadors themselves.

Furthermore, the Huguenots managed to establish themselves in Brazil and Florida, affecting Hispanic interests. Felipe II gathered a commission called Junta General, presided by Cardinal Espinosa, to analyze the situation described and to propose the corresponding solutions. The members of the Councils of State, of the Indies, of Orders, of the Chamber of Castile, and the Treasury were present, as well as some ecclesiastical authorities and Don Francisco de Toledo recently appointed Viceroy of Peru. Their meetings were held between August and December of 1568 and in them, the establishment of the Holy Office in the capitals of the two existing viceroyalties in the Indies (Lima and Mexico) was decided. Among the main motivations for the establishment of the Holy Office were the following:

As a result of the conquest, there had been a relaxation of public and private morals. The life of the Hispanics in the Indies was scandalous and there were many cases of polygamy, blasphemy, idolatry, witchcraft, etc. Because of this, the viceroyalty authorities as well as the town councils, the ecclesiastical authorities, and numerous personalities -among them Fray Bartolomé de las Casas- requested the King of Spain to establish the Inquisition to correct such deviations.

The prevailing anti-Semitism at that time in Spain was transferred to the Indian colonies along with the first peninsular conquerors and unquestionably, as time went by, the Judaizers bore the brunt of the Tribunal's operations. Very even though the crown had prohibited, from the first moments of the conquest, that the Jews and the Jewish converts, as well as their descendants, passed to their Indian dominions many of them had managed to circumvent such restrictions.

An instruction addressed in 1501 to the governor of Tierra Firme ordered him not to allow the presence of Jews, Moors, converts, heretics, or those reconciled by the Holy Office. After the composition of Seville (1509) the penitentiary converts were allowed to come to the Indies, and they were also authorized to trade. In 1518 such a license was left without effect and the prohibitions against them were renewed, although the periodic repetition of such measures clearly shows their non-compliance. The sanctions imposed on violators were the confiscation of their goods and banishment from the Indies.

When the expulsion of the Jews from Spain (1492) was decreed, many of them took refuge in Portugal. Later, when the unification of the crowns of Spain and Portugal took place during the reign of Philip II, their presence multiplied in the Spanish-American colonies, attracted by the search for the legendary riches they offered, as well as for greater freedom to continue practicing their ancestral rites, beliefs, and customs.

Another essential reason, for both religious and political motivations, was to avoid the propagation of Protestant sects. From a religious point of view, they could cause serious harm to the indigenous population by hindering, if not preventing, their conversion to the Catholic Religion, with the consequent detriment to their souls.

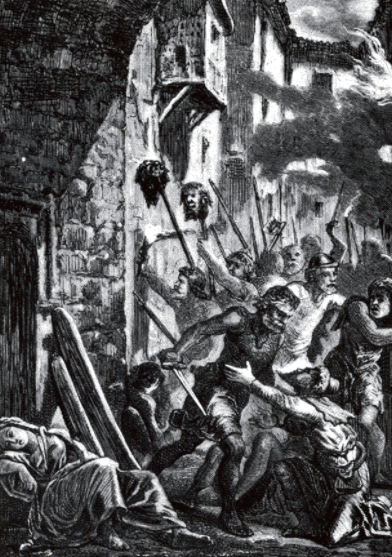

From a political point of view, if these sects were able to spread in the colonies, it would have led to the outbreak of religious revolts, similar to those faced by Emperor Charles V in Germany, which would have put Spanish rule at risk. The continuous attacks by Protestant corsairs and pirates -mainly English, Dutch and French- in which the atrocities they committed were fueled by their anti-Catholic religious convictions, had no other intention.

The corsairs and pirates not only attacked the Spanish ships to seize them and their merchandise, but they also kidnapped the crews and passengers to demand ransoms -in other cases, they sold them as slaves-, in addition to innumerable abuses and murders.

As if that were not enough, no coastal or near-coastal town was safe. This is demonstrated by the attacks carried out in Veracruz, Cartagena, Maracaibo, Santa Marta, Rancherías, Río de la Hacha, Santa María de los Remedios, Nombre de Dios, Callao, Paita, Havana, Puerto Rico, Santiago de Cuba, Santo Domingo, Jamaica, etc.

The common denominator of the pirates was that they were foreign Protestants animated by an unquenchable thirst for riches only comparable to their hatred of Spain and the Catholic Church. The vast majority of those prosecuted for such reasons were reconciled and treated benignly.

Incidentally, every religious organization - Protestant, Evangelical, Buddhist, Muslim, etc. - has its inquisition under different letterheads, which is an entity in charge of maintaining the fidelity of the members of the respective organization to their beliefs.

There were also occasions in which some people, voluntarily, presented themselves to confess, in which case they were treated with benevolence, sanctioning them only with some spiritual penalty and reconvening them so that they would not repeat this type of fault.

Just to mention a few names, let us remember John Hawkins, Francis Drake, Oxenham, Grenville, Raleigh, George Clifford, Winter, Francis Knollys, Martin Frobisher and Barker (English); Jean Terrier, Jacques Sore, and Francois le Clerc (French); Spilbergen and Piet Heyn (Dutch).