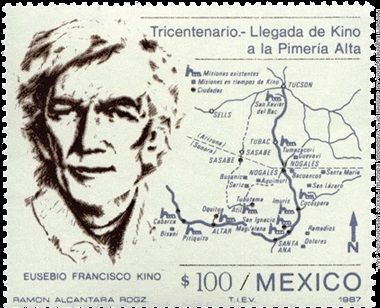

The main mission of Eusebio Francisco Kino's life, the spiritual conquest of the remote Pimería Alta

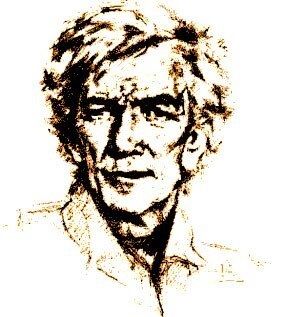

The life and work of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Italian-born Jesuit explorer, cartographer, astronomer, and a missionary, who led explorations in Baja California, Sonora, and Arizona.

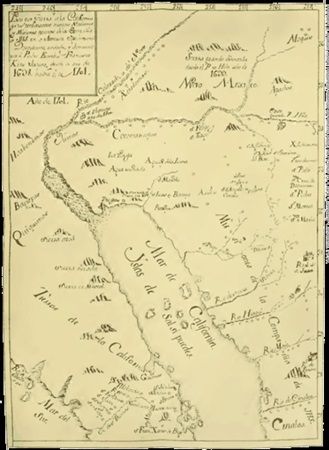

It is now twelve years and going on thirteen, that, having suspended the enterprise of the conquest and conversion of California... I find myself in this vast Pimería, which is more than 100 leagues long north-south and reaches from the province and valleys of Sonora to almost the province of Moqui, and as many and even more leagues wide from west to east or from east to west, from the lands of the Jocomes and Janos, Yumas and Apaches, and to the arm of the sea of California. Thus began Eusebio Francisco Kino's description of the colonization frontier that the Spaniards called Pimería Alta.

The name Pimería Alta derived from the name given that was applied to one of the indigenous groups or "tribes" that lived there: the Pimas. The name Alta was given because further down, that is, to the south, in the intermontane valleys of the Sierra Madre Occidental inhabited other peoples who were also called Pimas. As the Spaniards named according to the quadrature of the map, the southernmost were the ones below and the northernmost were the ones above or in the upper part of the map and that is why, without further discernment, the name remained as such.

Today we can more or less delimit the Pimería Alta of Kino's time as a vast territory that included a large part of the desert that is currently located in northern Sonora and southern Arizona, including the most fertile land that formed the courses of rivers that at that time were much more abundant and regular than today (the San Ignacio to the south, the Gila to the north and northwest, as well as the San Pedro and the Alto San Miguel to the south and southeast).

After passing through Cucurpe (which was then the northernmost Jesuit outpost), Kino arrived at an Indian ranchería called Cosari on March 13, 1687, on a day that was possibly Friday of Dolores and that is why he named the mission he would found in that place Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, which would be the main base of his missionary activity (on April 23, 1693, the solemn dedication of the temple of that mission took place). From there, Kino embarked on an intricate series of journeys that earned him a well-deserved reputation as an explorer, as he traveled thousands of miles back and forth to reach his goals. Surely, in many of those trips he was driven by the desire to find his way to California, which he achieved in 1702, when:

... with the four best mules we had, we climbed a hill to the west, where we could see the sea of California, and looking and seeing to the south and the west and southwest with and without a telescope with long sight, more than 30 leagues of flat land, without any sea, and the junction of the Colorado River with the Rio Grande (or Gila River...), its many groves and countryside... and returning to the place we ate, adding some sweets for consolation. ), its many groves and countryside ... and returning to the place we ate, adding some sweets for consolation that now, thanks to the Lord, we had given sight of the lands belonging to California, without there being any sea in between to separate these lands from it.

But he also explored towards the northeast to find a route that communicated the Pimería with the Moqui, that is to say, with New Mexico, where the Spaniards had already begun colonization about a century before. In addition to the discovery of precious metal mines, the possession of fertile land for agriculture and cattle ranching was an objective of the Spanish advance for which the Jesuit missions were outposts; hence Kino's interest in exploring parts of the Colorado River and its tributary, the Gila River.

This most abundant, most populous, and most fertile Colorado River, which without fail is the largest in all of New Spain, is the one that the ancient cosmographers called by antonomasia the river of the north, it is very likely of the Gran Quibira, and the truth is that through the fertile and pleasant lands of this great river you can enter as far as the Moquis ... According to weighing the sun with the astrolabe I have recognized ... that one reaches 36 degrees, which is the height at which the Moquis and missions belonging to New Mexico are located, and there will be no risk that the Apaches will impede the entrance from this part.

The indefatigable explorer also located several sites to install ports on the Sonoran coast and even had the luxury of directing, in Caborca, the construction of a small boat (Kino always had in mind the search for options so that the missions of Sonora and Sinaloa would support economically and materially the missionary project that his companion and friend, Father Juan María Salvatierra, was directing on the peninsula).

By July I entered the Soba nation, with Lieutenant Juan Matheo Mange, and we started a ship by cutting the timbers and some large planks. The other timbers, plans, and planks were cut here in Our Lady of Sorrows, to take all this ship to sea with mules, and there to assemble it, nail it, caulk it, embrocate it and pass on to nearby California.

Kino also attached great strategic importance to the consolidation of Spanish rule in the Pimería (which he called Nueva Navarra in honor of his patron saint Francisco Xavier, who had been born in Spanish Navarra), for he knew that the Russians, Dutch, English, and French intended to establish colonies on the Californian coast.

On other occasions, Kino would travel accompanied only by a couple of servants to fulfill his priestly duties, to administer the sacraments, say mass and instruct in the precepts of the Catholic faith to the Indian populations he encountered along the way. Some of his teaching methods may seem curious to us today, but he made use of the resources he had at hand and of explanations adjusted to what he knew:

The entrance was more than 80 leagues of the very flat road; I found the natives very affable and friendly, and in particular in the main ranchería of San Javier del Bac, which has about 800 souls: I spoke to them the word of God, and on the world map I showed them the lands and rivers and seas where we fathers came from far away to bring them the salutary teaching of our holy faith, and I told them how the Spaniards also formerly were not Christians, and that Santiago came to teach them the faith.

The ever studious Friar Eusebio took time to make inquiries of a type that today we would call "primitive archaeology", for example, when in November 1694 he visited some ruins in the vicinity of the Gila River about which he made the following conjectures:

The Casa Grande is a four-story building, as large as a castle and as big as the largest church in these lands of Sonora; it is said to have been left and depopulated by the elders of Moctezuma and, pursued by the nearby Apaches, they left to the east or Casas Grandes, and from there they went south and southwest and founded the great city and court of Mexico. Next to this Casa Grande, there are 13 other minor ones, somewhat more fallen, and the ruins of many other houses, which it was recognized that formerly there was here a city. On this occasion and on others afterwards I have known and heard, and sometimes seen ... the ruins of whole cities with many metates and broken pots, coals, etc.

As the Spaniards got to know the inhabitants of the Pimería Alta they became aware of some differences among them. What Kino and his contemporaries called "tribes" or "nations" were so only in the sense that they spoke the same language and shared some cultural traits, but none of them had socio-political organizations that integrated more than a few rancherías and in fact, these only joined together when there was a need for warfare or ceremonies. In the east of the Pimería, the communities practiced semi-sedentary agriculture, but in the desert, the groups were rather of nomadic gatherers and hunters; most of them were hostile to each other, especially when they did not speak the same language.

The Apaches, Janos, and Jocomes formed bands of warriors who constantly preyed on both other Indians and the Spaniards themselves. Despite this complex and chaotic situation, Kino was optimistic about the conversion of the Pimas and other "tribes" to Christianity and the ways of European civilization; but the Apaches and their allies he considered unredeemed enemies incapable of being included in the Christian fold. In his reports to the king, the Jesuit made it clear in whom he placed his confidence:

With these repeated many entries and missions that I made everywhere without particular expense to the Royal Treasury, there remain reduced to our friendship and obedience to the Royal Crown and the desire to receive our holy faith more than 30 000 souls of these contours, as well in this Pima nation, which has more than 16 000 souls, as in the nearby lands of the Cocomaricopas, Yumas, Quiquimas, Cutganes, Bagiopas, Hoabonomas, etc..., and many more are the other souls and peoples where one can enter with all ease, and I have already sent them collections and talks of Christian doctrine, and they have informed me and we know that when missionary fathers come they will follow and imitate these other nations already reduced.

Mission of peace, mission of war

From the beginning of the conquest of America, the Spanish Crown had three fundamental purposes with respect to the native inhabitants of the new continent: to convert them to Christianity, to civilize them under European cultural molds, and to exploit them socially and economically. Those who complied with these three precepts would be accepted as subjects of His Catholic Majesty with some rights and many more obligations. Those who did not would be considered enemies and war would be waged against them until submission or extermination.

In the frontier regions of the Empire, such as the Pimería, the mission system was the main means through which the State and the Church would impose their presence and would achieve - to varying degrees according to the specific circumstances of time and place - the realization of these purposes. In this way, and especially in northern New Spain, the mission was not only the site of religious indoctrination, but also the center of the congregation ("reduction") of the dispersed populations, the information gathering agency used by the Hispanics, the military outpost (since there were almost always some soldiers there to protect the priests) and, especially, the school where the acculturation processes that would transform the Indians came to life. Finally, it was an economic enterprise on the success of which the Indians' integration into the colonial system depended.

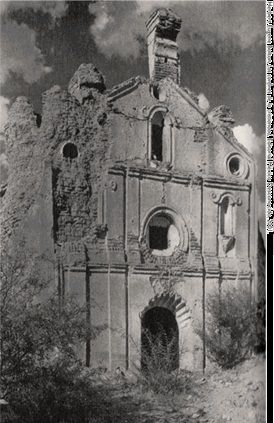

Eusebio Kino was an exemplary developer of the missionary method. First, he sent messages, through the indigenous people who had already allied themselves with him, to others who were in more distant lands. Then he would visit them in their homes and invite them to come to one of the missions -especially to Dolores- so that they could see for themselves the agricultural development and the material well-being they had achieved. Once he convinced them of the sincerity of his offer of friendship and of the economic advantages of association with the Christians, he proposed baptism and conversion. In this way he was able to found some 24 missions, among them: Dolores, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción de Caborca, Santa María Magdalena de Buquivaba, San José de Ímuris, San Pedro y San Pablo de Tubutama, San Marcelo de Sonoita, San Javier del Bac, San Cayetano de Tumacácori and others.

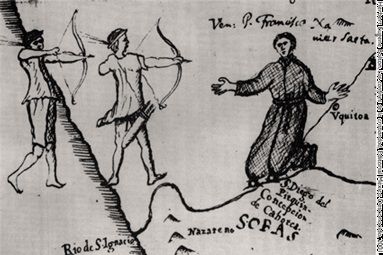

But although Kino and his fellow Jesuits could claim to have baptized about a thousand Pimas by 1689 (including several influential leaders) the situation was far from idyllic. Indigenous attacks on Spanish ranches increased in frequency; the settlers blamed the Pimas, whom they distrusted without distinguishing them from Apaches, Jocomes, and Janos. In Tubutama, the missionary of Czechoslovakian origin, Daniel Januske, placed in commanding positions in the mission of the Opata natives, who despised the Pimas for considering them savages; the bad treatments of those foremen overwhelmed the patience of the inhabitants of Tubutama who ended up murdering them; Januske himself was saved by fleeing hastily to San Ignacio. The revolted Pimas recruited people from other settlements and attacked Altar and Caborca, burning the missions and killing the Jesuit Francisco Javier Saeta and his assistants. Kino relates in this regard:

On April 2, 1695, Saturday of Glory, at sunrise, there entered the house of the V.P. [with this abbreviation, which means "your fatherhood," Kino refers to Father Saeta] those referred to as 40 malevolents of San Antonio Uquitoa, apparently in peace, but with their bows and arrows; they spoke with the V.P. and the V.P. with them, and the V.P. dismissed them amicably. with them, and dismissed them amicably; they went out and the V.P. came with them to the door of the little temple, where the V.P. then acknowledged their evil intent of the sacrilegious, and although the V.P. called the captain of the Concepcion [i.e., the indigenous authority of Caborca] but who from fear of the armed people did not come afterward; the V.P. He got down on his knees at the very door of his little church to receive, as he received, the two arrows, and getting up with them he went in to embrace a very beautiful Holy Christ that he had brought with him from Europe ... These cruel barbarians also killed the four servants of the V.P. One was named Francisco Javier, was a native of Ures, served as interpreter and was married to a Pima native of this Pimería called Lucía, a native of the large farm of Mototicachi, which so without cause was destroyed in the year of 1688, taking more than 20 prisoners from it to the royal that they call de los Frailes and killing more than 50 natives, only because of the suspicions that they were stealing horses and hostilities in this province, being particularly notorious now that it has always been done by the Jocomes, Janos, Yumas and Apaches and not by these so persecuted poor Pimas of this extensive Pimería around here....

The Spanish repression was not long in coming, without distinguishing between those who had actively participated in the revolt and those who had not; thus, many Pimas fled the missions for fear of being killed. The colonial authorities decided that Kino should arrange a meeting with the Pima leaders at a place called El Tupo. It was agreed that there the pacifist leaders would hand over the leaders of the revolt for trial. The Spanish soldiers were accompanied by a troop of Seri Indians. Then, in the middle of the meeting, a Spanish officer decapitated with his sword the first Pima pointed out as a rebel. Everyone tried to flee and a massacre was unleashed in which many Pimas were killed, among them several pacifist leaders to whom Kino had promised immunity.

The uprising spread and almost all the missions were burned, except Dolores, Remedios, and Cocóspera. Although the military power of the Spaniards had been demonstrated, their ineffectiveness in working together, missionaries and soldiers, as well as their lack of respect for their word, was also clear. Violence and distrust were introduced in the relations between Spaniards and natives, and the latter were divided into pro- and anti-Spanish. Despite these serious events, Kino's reputation as an honest man was somehow maintained among the Pimas. And so it was that he managed, not without difficulty, to conclude another pact that put an end to this first rebellion of the Pimas.

In the following years, Kino dedicated himself to working among the Pimas called Sobaipuris to the north of the Pimería Alta, in a region where a war against the Apaches was a frequent occurrence, which is why there are several and extensive references in Favores Celestiales ("Heavenly Favors") to conflicts with these barbaric Indians, whom the Jesuit called "the declared enemies of this province of Sonora:

At Quiburi I had a letter from the captain of the gentlemen soldiers, who were also arriving, and they arrived on the 9th of November [1697]. We found the Pima children of Quiburi very jovial and very friendly, and that they were dancing with the scalps and spoils of 15 Jocome and Jano enemies that a few days before they had killed, something that was so comforting to us that Captain Cristóbal Martín Bernal, and the ensign, and the sergeant and many others entered the wheel and danced happily in the company of the natives....

Contrary to what this chilling reference by Kino tells us, the Spaniards did not give determined and constant support to the Pima Sobaipuris in their fight against the Apaches, nor were permanent missions founded in their territory. Thus, as the pressure from the Apache bands increased, most of the Sobaipuris abandoned their settlements in the San Pedro Valley for good and went to live further east and north, where they were somewhat safer from the incursions of the nomadic tribesmen.

In the first decade of the 18th century, Kino dedicated his efforts to rebuilding the missionary system in the area of Caborca and San Ignacio, the area most damaged by the Pima revolt. He was aided in this task by other Jesuit missionaries, especially Luis Xavier Velarde and José Agustín Campos. But his progress was slow and Kino did not see the full results, for it was not until 1732 that the number of missionaries in the Pimería was increased.

Father Kino's legacy

Eusebio Francisco Kino died a natural death at the age of 66, almost at midnight on March 15, 1711, in the town of Santa María Magdalena, now Magdalena de Kino, Sonora, where he was buried. It is not known what caused his death, although there is news that he was suffering from "fevers" (probably malaria). He spent his last hours in the company of Father Campos, praying while lying on cow skins as a mattress, blankets as sheets, and a saddle as a pillow. We can think that among his last thoughts may have been his memories of his rides through the desert and the mountains to visit Indian ranches and of his practices as a geographer when he "weighed the sun with the astrolabe".

The historical importance of Kino has been judged from different points of view; the transcendence of his political work (as evangelizer and as colonizer) has been questioned, as well as the quality of saint that the local ecclesiastical hierarchy has tried to give him. But there is no doubt that in the popular mentality his fame is maintained to this day, in spite of the confusion there may be about considering him as a civil or religious hero.

For example, in Arizona and Sonora, Kino's name has been and is used in many establishments; hotels, pharmacies, hardware stores, parks, schools, boulevards, and even a bay and a city in Sonora. In the United States, Congress named him the founder of Arizona and authorized the placement of his statue in the National Statuary Hall of the Capitol in Washington, where each state in that country has two monuments honoring its distinguished citizens.

In 1966, research conducted by the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico and sponsored by the government of Sonora uncovered the remains of Kino that were buried under the Plaza de Armas of Magdalena. Since then, a monument was built there in honor of the Jesuit in which his skeleton can be seen. Moreover, Magdalena -today of Kino- is a place where a curious transposition takes place because on October 4 of every year the great feast and regional fair of San Francisco takes place. A multitude of pilgrims gathers there to pay tribute to the saint and thank him for the favors received. People come not only from Sonora and Arizona but also from other more distant places on both sides of the border. The Yaquis, Pimas, Pápagos, and other indigenous people also come to celebrate the saint.

However, among all there is some confusion about the historical identity of the divine personage who is worshipped; for some, it is St. Francis of Assisi (patron saint of the Franciscans, who replaced the Jesuits when they were expelled from New Spain in 1767, and whose day of celebration is precisely October 4); For others, it is the Francis of the Jesuits -Francisco Xavier- who were the ones who instituted the celebrations of Catholic saints in the past (and whose day of celebration is December 3, the date on which the feast was celebrated until the beginning of the 19th century); and for still others, it is the saint who walked through these lands performing miracles long ago, that is, Eusebio Francisco. Or perhaps for the majority of the faithful, it is a single being with three different manifestations or just one for that matter. The important thing is that next to the church where the miraculous image of San Francisco is found, the tomb of Kino is exposed, who thus - at least since the 1960s - has regained a place in the popular religiosity of the region.

But we now remember Kino as one of the most colorful explorers of North America: discoverer, astronomer, cartographer, historian, builder of missions and towns, priest, cattle magnate, promoter of agriculture and ranching, defender of the frontier, diplomat among the tribes, he also played an important role in the system of government established among the mission natives and even devoted time to the construction of ships. His biography is thus not only the story of a remarkable person, but also a source that helps to shed light on the cultural history of colonization and interethnic relations in the part of the western hemisphere that was called the Pimería Alta.

By Andrés Ortiz Garay, Source Correodelmaestro.com